When someone asks you what team you support and you reply with: ‘Rotherham United’, they’ll probably look at you with either pity, bewilderment, or disdain. The next thing they say will probably be: ‘yes, but what Premiership team do you support?’

You see, they want to talk about proper football.

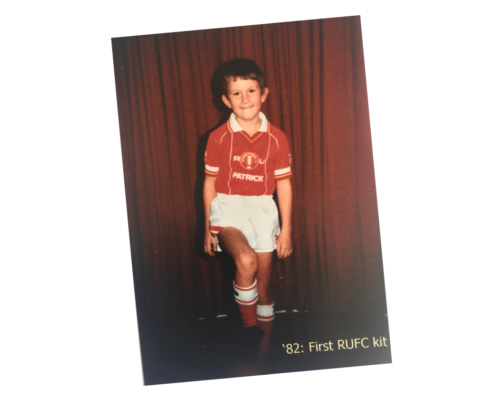

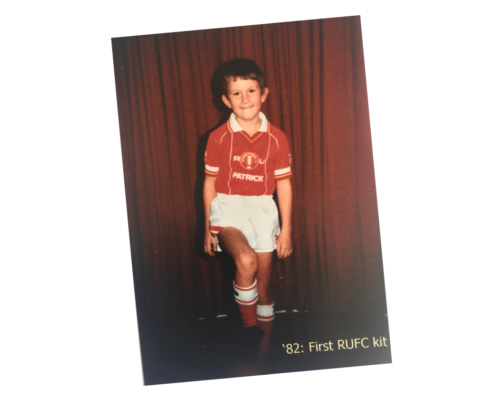

I started going to Rotherham matches when I was five years old. This was my dad’s fault. He’s a lifelong season ticket holder and, if you give him half a chance, he’ll proudly talk you through his collection of spreadsheets which detail every Rotherham United match since 1980. It’s all there: the result, the squad, the attendance, yellow cards, goalscorers, little graphs on league position from week to week. He’s an invaluable resource should you ever feel a pressing need to discover who came on as a sub in our 0-1 defeat against Darlington in 1996 (Jim Dobbin).

I got my own season ticket at nine and attended most home games until I moved away from South Yorkshire at 18. Even then, I caught as many matches as time, money and my location would allow – driving two hours on a freezing Tuesday night in February to sit in horizontal sleet while Rotherham hoofed out a belligerent 0-0 draw with Mansfield Town or Walsall.

Some of the bleakest moments of my life have been at Rotherham matches. But there have been some of the most joyful too, and I shared all these moments with the community of people around me. I may not have known their backgrounds or what they did for a living – or often even their names – but they were reliable, familiar faces that I saw week in, week out for decades. I’d grown up alongside them, changed with them, watched as they started bringing partners and eventually their own children. A woman who used to sit behind me hadn’t missed a home game in 50 years and she was still able to dance up and down the touchline like a teenager when we scored a last minute penalty to knock Sheffield United out of the Cup.

This was at Millmoor, a ground where you usually couldn’t get advance tickets for matches because the one printer they had in the office was invariably broken. Right up until 2008 when the team moved stadiums, many of the advertising hoardings around the pitch still encouraged you to ring numbers that hadn’t existed since the area code changed in 1994 and the lavatory was a concrete wall behind the main stand that had a shallow trough dug into the floor and the word ‘tiolets’ written on it in chalk. During one of our brief visits to the upper leagues in the late 90s, a corporate hospitality area was added. It consisted of six portacabins painted red and stacked precariously on top of one another.

‘Yes, but what Premiership team do you support?’

I don’t have the first clue what the Premiership table looks like and, to be honest, I’d be hard pressed to name many of the clubs in that league with any degree of certainty. I don’t care who’s likely to win the league or qualify for the European Cup or play in the FA Cup final – the most a lower league supporter can hope for is reaching the third round where you might get drawn against a big Premiership club.

This happened for Rotherham United in 2001. We were drawn against Liverpool and the mass euphoria in Rotherham was probably greater than in Liverpool when they won the UEFA Cup. Of course, we lost the game itself. That wasn’t important though. What mattered was that we had a big day out at Anfield and our team battled with passion and pride – our £75 a week YTS lad man-marking a £60,000 per week Liverpool striker and keeping him out of the game. Success is relative and, when you support a lower league team, you have to recalibrate your expectations.

You get used to the club never having any money and scrabbling around to build a squad from free transfers. You get used to watching promising young players develop over years only to get snapped up for a pittance by a bigger club as soon as they show the first sign of any flair. You get used to not seeing your team on television or hearing the commentary on the radio, you get used to dismissive match reports on sports websites and always being ‘the opposition’ for the team that’s actually the focus – even when you do win, it’ll be because the other side played badly rather than your team’s performance.

You also get used to people’s expressions of pity or bewilderment or disdain when you tell them what team you support. You see, they want to talk about proper football.